#21 On Reading Susan Sontag

Winter Sunrise, from Lone Pine (1944) by Ansel Adams [For more about this photo tune into Episode #20]

On Photography, by Susan Sontag [view PDF]

But being educated by photographs is not like being educated by older, more artisanal images. For one thing, there are a great many more images around, claiming our attention. The inventory started in 1839 and since then just about everything has been photographed, or so it seems. … In teaching us a new visual code, photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe. They are a grammar and, even more importantly, an ethics of seeing. (Sontag, from On Photography)

A young man in curlers at home on West 20th Street, N.Y.C. 1966

Photos by Diane Arbus

Diane Arbus giving a talk at RISD in 1970, by Stephen A. Frank

Identical Twins, Roselle, New Jersey, 1967

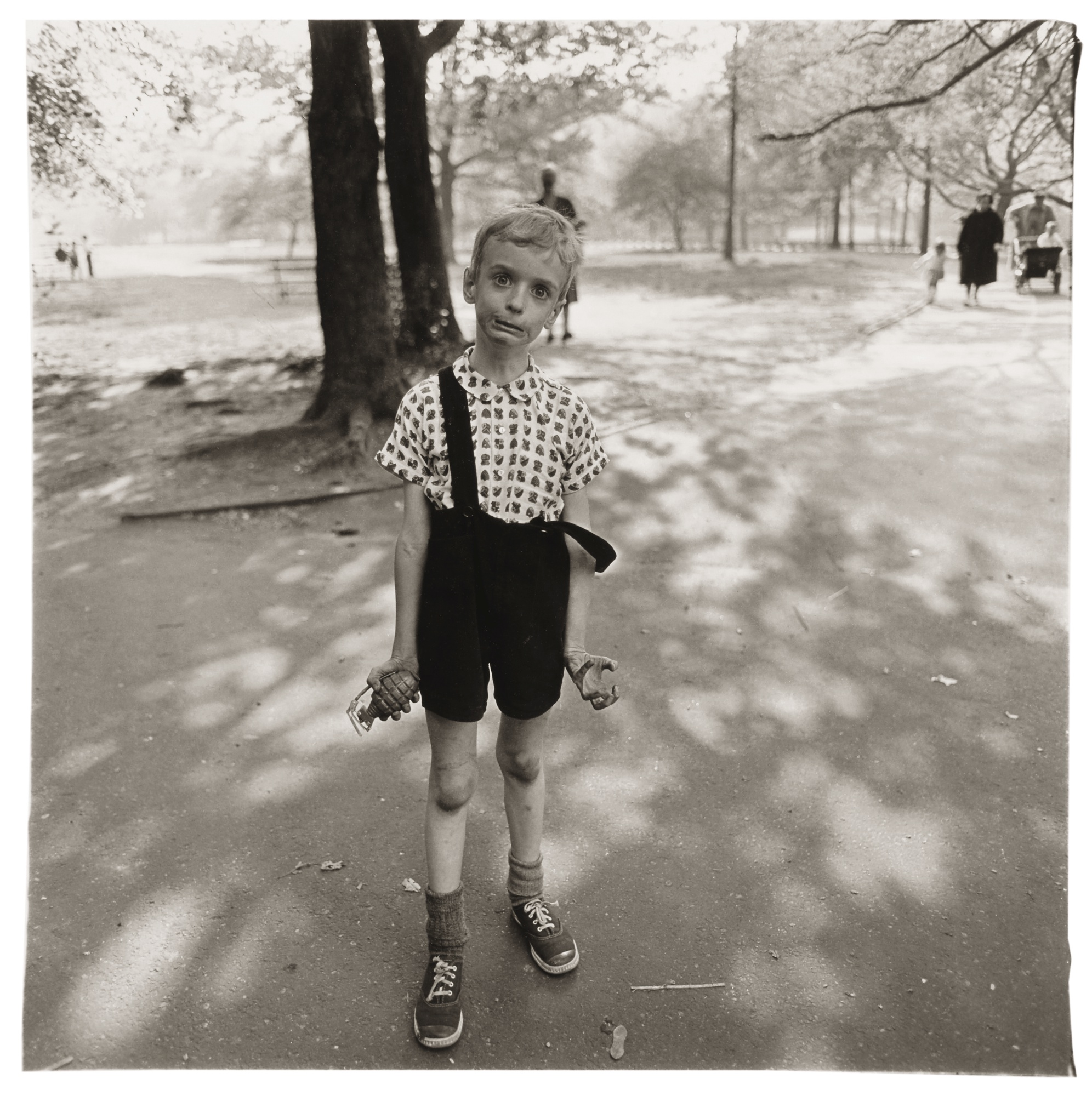

Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, NYC, 1962

Edward Steichen, 1915

In photography’s early decades, photographs were expected to be idealized images. This is still the aim of most amateur photographers, for whom a beautiful photograph is a photograph of something beautiful, like a woman, a sunset. In 1915 Edward Steichen photographed a milk bottle on a tenement fire escape, an early example of a quite different idea of the beautiful photograph. And since the 1920s, ambitious professionals, those whose work gets into museums, have steadily drifted away from lyrical subjects, conscientiously exploring plain, tawdry, or even vapid material. In recent decades, photography has succeeded in somewhat revising, for everybody, the definitions of what is beautiful and ugly—along the lines that Whitman had proposed. If (in Whitman’s words) “each precise object or condition or combination or process exhibits a beauty,” it becomes superficial to single out some things as beautiful and others as not. If “all that a person does or thinks is of consequence,” it becomes arbitrary to treat some moments in life as important and most as trivial. (Sontag)

Legends of photography. Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham and Jerry Uelsmann. Photo by Ted Orland, 1969

Art and Fear, by David Bayles and Ted Orland

From the Introduction:

THIS IS A BOOK ABOUT MAKING ART. Ordinary art. Ordinary art means something like: all art not made by Mozart. After all, art is rarely made by Mozart-like people — essentially (statistically speaking) there aren't any people like that. But while geniuses may get made once-a-century or so, good art gets made all the time. Making art is a common and intimately human activity, filled with all the perils (and rewards) that accompany any worthwhile effort. The difficulties artmakers face are not remote and heroic, but universal and familiar.

One and a Half Domes, Yosemite (1975), by Ted Orland

Rubin’s Portfolio of Photography | Rubin’s Instagram (@droidmaker)

Suzanne’s Instagram (@sfritzhanson)

If you like the show, please subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or your favorite podcasting app, and please rate the podcast. And don’t forget to join the Neomodern Facebook group to discuss the show, share your photos, hear about specials for printing or framing your best images. Thank you!

![Winter Sunrise, from Lone Pine (1944) by Ansel Adams [For more about this photo tune into Episode #20]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5978aa8103596e3ee467ee27/1540538600260-IKD5J1LX2B6NC79CCPUO/1901018-2.jpg)