#59 Meet Doug Menuez, "Fearless Genius" Photojournalist

“Art is anything you can get away with.”

Marshall McLuhan (and Andy Warhol)

Who is Doug Menuez?

Documentary photographer and director Doug Menuez once stood at the North Pole, crossed the Sahara, had tea with Stalin's daughter and held a chunk of Einstein's brain. Quitting his blues band in 1981, he began his career freelancing for Time, LIFE, Newsweek, Fortune, USA Today, the New York Times Magazine and many other publications. He covered the AIDS crisis, homelessness in America, politics, five Super Bowls and the Olympics. His portrait assignments included Presidents Bush, Sr. and Clinton, Cate Blanchett, Robert Redford, Lenny Kravitz, Mother Teresa, Jane Goodall and Hugh Jackman. His award-winning advertising campaigns and corporate projects for global brands include Chevrolet, FedEx, Nikon, GE, Chevron, HP, Coca Cola, Emirates Airlines, Charles Schwab and Microsoft.

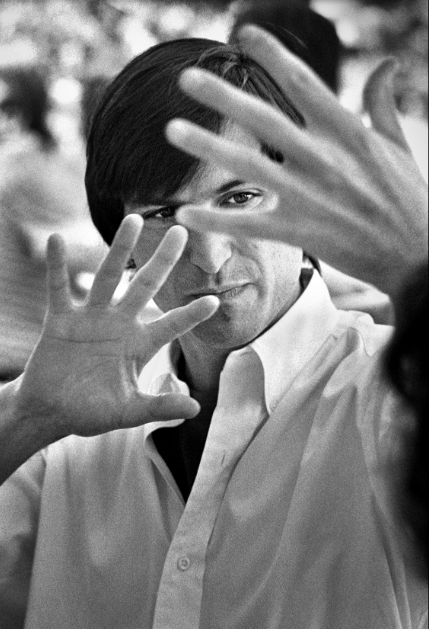

His fourth book, “Fearless Genius: The Digital Revolution in Silicon Valley 1985-2000,” by Simon & Schuster’s Atria Books, became a #1 bestseller on Amazon’s photo book list and was published in the US, Japan, the UK, South Korea and China. Over 100 million people worldwide have seen the project through the book, exhibits, viral press and talks. A fine art exhibition of rare images of Silicon Valley’s greatest innovators, including Steve Jobs, as they changed our world continues to travel. His extensive archive of over one million images was acquired by Stanford University Libraries in 2004. Doug divides his time between the Hudson Valley and NYC.

Doug Menuez, “Steve Jobs Returning from an Employee Picnic. Santa Cruz Highway, California” (1987)

Doug Menuez. “Steve Jobs Explaining Ten Year Technology. Development Cycles. Sonoma, California” (1986)

Doug Menuez, “Steve Jobs Rallies the Troops” (1986)

Doug Menuez, “Steve Jobs Considers a Response. Palo Alto, California” (1986)

Doug Menuez, “The Founders of Adobe Systems Preparing to Release Photoshop. Mountain View, California” (1988)

“We’re primates—we look for eyes, expression and emotion in the human face. The face is how we connect with people.” — Doug Menuez

ON THE WALL OF DOUG MENUEZ

Doug Menuez, “Hacienda de San José del Refugio Amatitan” (2001), from his book “Heaven, Earth, Tequilla”

Elliott Erwitt, “California Kiss, Santa Monica, CA” (1955)

Rubin “Elliott Erwitt” (2011)

Menuez has balanced the commercial and the art in photography. “The main point remains that during the entire history of photography there has been a constant debate about it being art or not. Avedon merged art and commerce, as did Steichen decades before him as he fought this battle. Today the result is people are making editions of 1 to create the one of a kind object. Young collectors don’t give a shit, but there are still [only] about 100 serious fine art photo collectors in the US.”

The Concerned Photographer (on Amazon)

W. Eugene Smith, master of the photo story. Not ashamed of moving people, or sandwiching negatives… but he made a clear point that he was an artist.

It was the truth as he saw it.

Smith, “Welsh Minors, Wales” (1950)

A0825

Smith, “Walk to Paradise Garden” (1946)

A0824

A nice story about W. Eugene Smith and his photo “Walk to Paradise Garden”

https://huxleyparlour.com/w-eugene-smith-hope-and-innocence-2/

Vignetting

Here’s an example of vignetting (from https://filmora.wondershare.com/video-editing-tips/add-vignette-effect-to-video.html). It’s a strange effect, oddly hard to notice when done well. It also can be applied heavily and look odd.

Rubin “Fleet Week” (2011)

Vignetting is a form of cropping, but using the darkening function around the edges to narrow the viewers view, almost like looking down a tube at the photo. Here’s a more subtle version of vignetting, where the entire image (except the two men) has been burned in, with the lower area of the street and the upper left, both pushed even more, to make the subjects draw your eye a little better.

“The best camera is the one you have with you.”

—Chase Jarvis (Visionary photographer, director, and social artist)

The Leica M. A precision tool. Without a lens it’s somewhere between $5-8K. I’ve seen side-by-side comparisons of Leica photos and iPhone photos, and in many cases the images are comparable (which is amazing); but the Leica is still a precision optical device and there’s more to a great shot than the resolution of the output.

Dorthea Lange, “Migrant Mother” (1936)

Such a classic, and sensitive, image from Lange. Oh, and less widely known in that she retouched the photo to remove some stuff in the lower right. Like Adams, photographers weren’t so sensitive about using a pencil or needle to clean up negatives.

https://iconicphotos.wordpress.com/2009/04/22/migrant-mother/

Dorthea Lange, “Migrant Mother” (1936) — and other shots from that shoot.

Transcript

Rubin: Hey Suzanne.

Suzanne: Hey, Rubin. How are you?

Rubin: I'm great. I'm really excited to introduce you to a kind of a great photographer friend of mine, Doug Menuez. This is Suzanne. Suzanne. Doug. Good morning. Hi, how are you?

Menuez: Good to see you too, Michael. Thank you.

Rubin: It's great to see you. Um, I wanted to just introduce you a little bit to our audience. Um, you are an unbelievable photo journalist and, um, yeah, and I think the thing I wanted to say most, uh, you're known for covering the sort of the birth and explosion of Silicon Valley starting in the 80s. Um, and I want to say as a collector of photography, there are certain classic photos in civilization. You know, Margaret Burke White's pictures of Gandhi or you know, Cartier Bresson shooting Martin Luther King's rally. And I swear your pictures of the creation, uh, with Steve Jobs are among those pictures. They are going to be part of the, the history of photography forever. And it's just wonderful to know you and like, I'm kind of little, a little emotional, a fan going right now.

Menuez: We have to end this interview right now. We compose myself, you know, listen, I'm grateful, so grateful because we all want to reach our audience. You know, you work hard to make these images that connect with people, saw him. I'm hugely flattered and I'm really moved by that. Beautiful. Thank you. Compliment. And I mean obviously, um, I try to stay humble because whenever I don't, then God crushes me like a bug on the windscreen. But that was a pretty good compliment. Thanks Mike.

Rubin: Nice. Well you are an amazing photo journalist and um, but one of the things, I mean I think people can tune into some of your great talks about fearless genius or about some of your new work, but our audience, our target, our audience, our consumers. There are just people with iPhones. And so a lot of what I want to talk to you about it just your relationship to photography, you know, and, and how you feel about it. And I suppose the first thing I'd, I'd just like to ask you is, um, well actually so many things you've resist calling yourself an artist. I've noticed like you, you say you're a visual storyteller. What is that?

Menuez: Uh, I went back to artists today on Instagram,

Rubin: Graham.

Menuez: I mean, who isnt conflicted in the visual and creative world, right? You know, this is a therapy issue, but no, I mean since I was 10 years old, I want it to be an artist. I was studying painting and we'd go to the Museum of modern art and look at Matisse and Picasso. And then I discovered photography. My father gave me a camera and also the concern photographer, the beautiful book with the Magnet Starvis when I was 12 so I knew that was my, my medium and I embrace it. And I think in photography as I was growing up, it wasn't considered art. You know, and I went to art school and it was always suspect and the big issue was really came down to collect your valuation because you could make multiple prints. It wasn't the object. So I internalized this conflict in the world.

Menuez: I mean, when I was around 10 or 11 Avedon's print of Princess bore gazing was accepted in the collection, the permanent collection. It was the museum, Modern Art. And it was a big scandal because he was in the times, they described it as a commercial photographer. And so, you know, this is a never ending thing, but I do feel like I've always wanted to be an artist. I went to art school all the way I talk about it now is as a documentary photographer working in telling stories, I basically am saying this is a subjective truth, this is how I see it and no one can tell me they can be truly objective. You know I, I worked for the magazine is time and life and Newsweek and I saw a lot of occasions where objectivity was not employed. It's just so hard. So I think what I think an artist does is they feel compelled to express something within themselves. And that's what I do visually through the camera. And thanks for letting me,

Rubin: but you, you go back and forth. Can you talk a lot about, you've managed to create a balance that few have between being an artist and being a commercial photographer. How do you do that? Like how do you not fall too deeply into one side or the other?

Menuez: Well, you know, another way that I access this is through Andy Warhol who said, art is whatever you can get away with. Um, I really see, I really feel like there's, the question that you're asking is how do you reconcile the work that you feel called to do that gives you passion that you're passionate about, that gives you joy and the work you must do to make a living. And there is a lot of misconceptions about the ladder in terms of how you get it. And I figured out, I guess in the late nineties after being a photo journalist for a long time, and then the change that was happening in advertising was they were looking for authenticity. The audience was looking for more authenticity and was shifting from aspirational. Get this portion you can be groovy to, oh, that experience I can relate to. Maybe this is a really good product. I slow.

Menuez: Yeah. I think, I think that was an important cultural shift as the audience became hip to being manipulated. I think there's partly the digital revolution. Anyway, I just saw an opportunity there and I thought it was a chance actually to kind of go back to art school in that I could reconcile the conflict by defining myself in the commercial space. This is what I do. This is how I see you can exploit that. You can use me, uh, to a certain amount. I can be useful for you, but this is how it is. I shoot, I don't change my eye or how I shoot, which was the thing. A lot of times people would get hired because of their name and then in the commercial project they would have them shoot something completely, uh, you know, antithetical to what they stood for. So it was always horrible, but they did it for the money. So I decided I wanted to wake up in the morning and be a photographer, whether I was taking pictures of my kid or I was doing a commercial assignment or a commission to do a portrait of someone or a longterm documentary project. So that was how I did it.

Rubin: Do you, um, do you have any issues with photo manipulation tools like Photoshop? Where do you draw the line? Is there a line where you foot manipulate anything or do you not manipulate or what's, okay, sorry. That's it.

Menuez: This is, this is such an important question and it's also cyclical. And you know, when I was starting out on newspapers in the 70s, um, we would hear stories about photographers in the forties using pencils to change pictures and then transmitting them. I heard stories in the 60s people doing that. And even in the 70s, people were, they were manipulating photographs here and there. People were cheating, if you will. We took an oath. I remember the NPPA, the NPPA had a, uh, a manifesto you had to sign or you had to read to be a member that you would always tell the truth, you would manipulate your photos. Um, but then, you know, one of my greatest influences and inspirations was a photographer named w Eugene Smith and Jane Smith was the father of the photo essay more or less in life magazine. He was the king of that. And when I was 17, I actually got to meet him and hear him talk and then show him my work. And one of the things he talked about was he wasn't ashamed of having moved people towards the window. He wasn't ashamed of having sandwiches negative. It was like, you know, it's fact relig that he would manipulate. But he made it very clear point that he felt that he was an artist. He had a letter from Ansel Adam saying he was an artist.

Rubin: She read a certified, I certified the certification.

Menuez: He wanted that, that validation, it seemed, and he really believed that it was the truth as he saw it. And that was the best he could do. That's how he did it. So I always had that in my mind and then jump forward from, uh, that to being an intern at the Washington Post and in the dark room, we all had a little vile of potassium, fair, Sinai, deadly poison, and next to our fixer. So that when we were finishing our prints or I and the developer, we could bleach and highlights or narrows more than we could move if we were dodging. So we were dodging and burning all newspaper for starters. We're doing that because you had 60 line screens, right? You could barely see the photo anyway. So you're trying to make lights and darks to move your eye. Your eye goes to the lightest area of the picture.

Menuez: This is a really important point for all your listeners. This is the law of physics here. Your eye will go to the lightest area. So that's where you want to have the emotional impact. That's what we want of this center of interest. Right? And, and if it's light around the edges, you're, I just flies right off and you're onto the next thing somewhere else. You're gone until we wedding. Right? Hence vignetting, hence vignetting. And it's a way to move through the user's eye without them realizing it. So it's always been about manipulating the viewers a response and being able to see the information clearly and quickly. Now, has that been abused? Yeah, it's been so much, so much. And uh, with Photoshop, you know, I guess the short answer would be if you want to cut all that out, the sure. The short answer would be, as Russell Brown famously said, when he was being attacked, when Photoshop was being productized, hey, this is a hammer with this.

Menuez: You can build a house or you can tear it down. It's just a tool. You know, I, I heard him say, we've talked to him yet last week and um, he said that exact thing, but it's not, but it's not, I'm not sure I totally agree with that because to abdicate all responsibility, like whatever you make with this is we're convincing people of something. You know, people absorb. It's like a, uh, a chemical that goes through the blood brain barrier. Like it gets to sneak through and you perceive it as truth and as an artist, of course, your truth that you know, you're communicating your truth, but it has a journalist. Of course you're supposed to sort of have objective objectivity, but we know no foot photograph is objective. It's, it's, it's a fallacy from, it's from the premise, right.

Suzanne: I was just going to say does it also depend on kind of the, the um, the moral standards of the person making it like the w with the hammer reference is that person needs, you are either going to build something or they're going to like tear it down and it's what they're intending to do with it. If you have every intention of trying to fool people, that's what you're bringing to that. And it's hard for the audience to have to like to decipher that it's, but it's kind of wrong on that, on that person's, uh, intention of like, I want to fool people with photo journalism. That seems wrong. If you're making art...

Rubin: Suzanne, Doug, the, the famous picture from National Geographic where they moved to the pyramids slightly to fit it on their vertical format. You have any issue with that? Is that okay? I will decline comment on that. But I would say this, I want to go back to when I said the way behind my statement of Russell's about the hammer, the tool of this a tool was an assumption that we have a social contract that we will use it for. Good to Suzanne's point, journalists work really hard to get at the truth and this is not respected today in America obviously. Yeah. And I, I really feel like this is a sacred trust that the creators and the writers have to have with their audience to make this, it's a social contract, so yeah. Yeah. I feel like that's what what we have to remember. And that means you got to make an effort to keep that contract on both sides. It's a meeting of the minds and digital technology has weakened that contract because people don't know what to trust.

Menuez: And if it's, and by the way, the cover of a book or a magazine, it's got two seconds to catch your eye. And so you, and it's more of an ad than it is editorial content. So I'm confused myself about where the lines should be drawn for that I technically would prefer not to change anything for a journalistic publication ever. But there's, you know, I'm a person who lives with gray areas. I refuse to see everything as black and white. One of the things you learn in journalism, you go at it and you get both sides of the story and then there's five sides to the story.

Rubin: Right? Right. You're famously a user of the Leica Camera, and of course it's a beautiful camera. How do you feel about iPhone, smartphone photography? Do you take pictures with your smartphone? What do, what do you think about that stuff? Does tell us the device matter. Okay.

Menuez: I, I, I love that a billion smartphones came online last year and that unleashed untold amounts of human creativity with that camera. I salute Miraco borogoves Gove and her team at apple who sweated bullets to really make that camera's sing and transform the world. I think that, um, having a camera in my phone, it's like Chase Jarvis said the best cameras and when you have whiskey with freaking count on this cat, right. Love this camera. And I love my likeness and the like is are astonishing me every day because they are, um, they, they put nothing in, they don't need. So it, it's re re energize me by forcing an original discipline of what photography was to me. A lot of the craft is, um, brought to the fore and it also leverages my brain in a way that other cameras don't because the menus and the user interface is so sweet, so clean and so clear that I can actually use the features of the camera. Previously I would ignore all the minis mini options because I could never remember where those things, yeah,

Rubin: nested 19. You'd have to do it fast, like in job after you missed the fricking fixtures. So I would hand it to my assistant and say, where's that thing? And then I would use the other camera until he found me to hand it to me last night. It.

Menuez: So this camera, I, my assistant said to me the first day we used it, we were shooting a hackathon. Um, or maybe this was the second time I use it, this is the Leica sl. And he came to me, it was a 48 hour shoot. And he came to me in the middle of that and he said, you know, is there something wrong? I said, no, what's the matter? He goes, well, you're only shooting half as much as you always do. I was like, what? And I went to look at the material and I was like, oh, it's better. And we kept more selects and we shot half as much. So you know, I, I feel like the tool, like we say, like I said in my, one of my videos is stop. We always say it's not the camera, it's subsurface service, but hey, if that tool is a good match for your brain and how you work, by all means that's going to increase your chances of getting better pictures and be a better photographer. So you have to find the right tool for you.

Rubin: Yeah, I will take, wait, can I ask one more follow up on that? Which is I'm afraid of a Leica. Like I keep going to the liquor store and I pull them out and I hold them and I sort of fetishize this thing. It's, it just feels so good. It's like having a slide rule or, uh, uh, a great device in your hand that's perfectly tooled. I'm terrified. Half of my pictures, I'm standing in the waves. I'm like, it's raining on me. And I think I would be too concerned about this beautiful expensive precision device getting destroyed. And I prefer having kind of a beater for being out in the world. Am I?

Menuez: I buy you stuff all the time and by the time I get through with something in two years, it's already, the brass has rubbed off and it's already a beater. I just think there's, you know, I haven't been in love with a camera since I was like 14, but what a joy when you do fall. I fell in love with this, but I still don't treat it any differently than a hammer. It's my tool. And I maybe I cheated a little bit better than the last previous cameras, but not much. You know? And I feel like they have to be built to, they are, I mean this is the beauty of these. You can use these for photography or as a weapon. You know, there's so what made, so I kind of think you have to let go of that. That is a fetish that isn't objectification of the tool.

Menuez: But you know, if it's, if it helps buy used stuff by beat up stuff already get a good price, then you won't feel worried about it. Because I think a lot of people who are new or who are not coming at it from a professional point of view, who have having a run down the street with their cameras banging together with a mob chasing you. You know, you get over that heart of Oh this is a really special thing. You get over the money because you don't think about the money. You just think about the cameras. I appreciate people who take care of their cameras. And I know a lot of professionals who are really meticulous with it. They typically are not news photographer who are in the Sahara or at the North Pole or whatever. It's just hard to that and you just buy a new one if it, it's gone. You know,

Suzanne: speaking of running down the street, I was watching one of your Leica videos and um, it struck me as you don't do like photo walks as much as photo runs I chasing after the action that you see mid interview to get the shot. Can you talk a little bit more about just being willing to improvise like that? Huh.

Menuez: I can't really, it's just things happen and you have to re train. Our training is too,

Rubin: uh,

Menuez: get that picture no matter what. And it's so hard and they're so fleeting. It's so hard. Every one is a miracle. Every single frame that works, it's a miracle from God, you know? So I make, I can't explain it other than I'm just obsessed, you know, I'm just trying, I'm trying really hard and, and I'm failing. You know, 95% of the time I'm failing. Okay. So that's why he's so fearful when you get the design,

Rubin: but you're judged by the 5% dude, 5% or stuck are stellar. So it doesn't matter how many times you've missed.

Menuez: Yeah, but I think that's a good point though. I think if you practice this sort of zen approach of being in the moment, don't look at the histogram, don't worry about the LCD. And if you want to be a good street photography, you really have to have your head on a swivel and you have to feel things and just get in tune with where you are. And after a while things will come to you. It's a universal law.

Suzanne: Do you know when you take that shot? Like I'd got it. Okay.

Menuez: If you do, you didn't get it unless you're shooting a mirrorless camera. Because the thing is is that the mirror was always up at the millisecond. Second. So when I was shooting hard news or sports, if I, if I was really happy and then I would realize, oh, you know, I was in a millisecond later. Then you process the filming, you find out the truth and you know there's a, there's a really good book about Pulitzer Prize photos and you can see they put side by side,

Rubin: there's like

Menuez: 10 photographers at an event shooting the same thing and yet the one that got the Pulitzer is just a millisecond layer. Then the one that's the photographer to the left, somehow it resonates more with the viewers. So with the mirrorless camera you do see it, but it's also going so fast, you're really not sure. I think what I, I think I would say 99% of the time I'm right when I think I got it. You don't really know for sure.

Rubin: How do you think about, um, I mean a lot of what you're describing sounds like a timing, right? To getting that right instant and I, of course that's an important part, but the other part is composition. How do you think about composition? Is it a natural thing? Is it just filling the frame with pieces? Can, can it be taught? How much time do you have? If you've got the answer, we'll keep the hoarding.

Menuez: I was happy to do it. When we were living in Woodstock at our house with Dennis stock, Great Magnum photographers, shut James Dean and all those beautiful cultural pictures he did.

Rubin: Rodney stock worked with me back in day at Lucasfilm. Yeah.

Menuez: Oh God. Yeah. Oh, what a small world anyway. Oh my God. Yeah. So Dennis, we're sitting at this very table, which is our old dining room table. And we were having an argument about contemporary fine art photography. I was on the board at the center for Photography and Dennis was a supporter and he was feeling like modern contemporary photography was just total bullshit. And the reason was is the composition and Dah, Dah, Dah. And I said, well, Dennis rules are made to be broken. And he slammed. That's bullshit. Do you want your pictures to be memorable? I was like, well yeah, definitely too. Well exactly. So, and he said, well go back to the 20th century favorites.

Menuez: So your favorite pictures that stuck with you, that you love the most, that changed your life. And you will see in every single one of those pictures, Aristotle's golden mean expressed.

Rubin: I don't buy it.

Menuez: I went back and he was 100% right. 100% right. Go look at the golden mean. Anyway. I still believe rules are made to be broken. And if it works, it works. Like there are some contrary things you can do. But here's my next point. When I was doing that study, it occurred to me to ask the question, why does still photography even exist today with this video centric world? And this was about 2007 when we were having this discussion. And I thought it was the time where everyone was telling me you have to shoot video and stills at the same time. I'm like, impossible, but why? You know, and stills, we're going down videos coming up and you know, people have much more engagement on sites with video Dada.

Menuez: But why does this still persist? Why is it still here? And I thought about it and I thought about it and I started to realize that I was remembering a dream and I think we think of dreams is like movies and I was remembering a dream and it came down to this moment in the dream that actually translated as like a scene of frame from the dream and my mind was filling in what had happened before and I remember what happened after, but I was fixated on this one scene and then I tried to think about what came next and it was another scene in my, when I really concentrated on this really deeply meditated on it. And then I thought about films and when I remembered films I'm remembering also seeing St St, which is frame frame frame. And we tend in science to recreate biology over and over and over in the history of science fiction and science.

Menuez: We are constantly recreating. That's what we're doing right now with Ai. We're trying to recreate the brain. Okay, what if the still photograph is the perfect Dataset for absorbing information for our brains? You know, you open your eyes and everything's upside down and black and white and then it becomes color at your, you're scanning for fight or flight, right? And then you start, your brain fills in and we're actually only seeing a percent small percentage of what's really there are bank can't accept all the data. What if that's still okay? So if I'm right about that, and by the way, I've talked to brain scientists and there isn't a lot of research. You can't really go online and find out easily how visual memory is formed. We know where a lot more about it now than we did when I started this query because I hired a researcher and I couldn't find anything about visual memory.

Menuez: We've learned a lot about all kinds of memory, but we still don't know a lot about visual memory. We know enough to know kind of where it is, but not how it's formed and not this theory. So what if I'm right? That means composition matters a hell of a lot. It makes the pictures sticky. Next question. So take pictures. What would, what would be your stickiest picture that, that you've taken? What is the picture that you want to be stuck in everyone's minds you want to be remembered for? I know, I really can't answer that. I have a million and a half of images in my archive is Stanford side. I don't, I'm, I'm not, I don't even have, I can't even tell you because I'm going through pictures now from 10 years ago. I never even saw or 20 years ago that I never even saw. We would shoot it and ship it and it takes me on average a year just to decide which pictures I liked from a shoot I did today.

Menuez: Yeah. I'm still processing it. Well, I, I use an artificial part of me that's very, um, trained, um, from being on deadlines and submitting, you know, and that's based on not me. That's not my internal clock. That's an audience thing. I mean, we were shooting for, for Newsweek, you're shooting for 3 million readers at the day back in the day. And so they're going to use a picture that's actually more to the lowest common denominator. That's quicker read as quicker and more compelling. Emotionally. I think for me, given the conflict I was explaining to you about being an artist versus telling a story for an audience, that's my biggest problem is what do I, you know, I'm always trying to ask myself what really is exciting for me versus what I know will work to reach an audience. So I'm still working that out. I need, I can't answer that Susan, but I think it's, but I think it's fun when you ask about composition and I always tell like students in classes that you learn the rules. Like you know, Dennis said learn the rules and then experiment. You just go out and play. I don't think there is any reason not to break the rules. I don't,

Rubin: I mean one of my soap boxes on the podcast is that I don't think there are, I just don't, I feel like, I feel like your job as a photographer is to fit all the things you want in the frame artfully and, and they're not going to be following leading lines of rules of thirds or any of that. You didn't need to get the things in there and they have the right kind of balances between them. I Dunno. It's, I don't think it can be taught that way. I think it would distract a beginner with, they're thinking about things like rules of thirds or no, you just want to, sometimes the subjects in the center and sometimes the subjects off center, you know, that's a, that's a thing, but I don't say that good. It's, is it a third and a quarter like come on. That's like a, it's a kind of a ridiculous thing to put in someone's head. Just move it, move the subject around, move everything around. You know,

Suzanne: Ruben, sometimes you feel like it's also Monday, like Monday quarterback Chi or Monday quarterbacking where you're like, oh well I'm going to look at this. I'm going to look at this picture again. And now it's kind of a third. So it's the rule of thirds. That's why I like it. Right. Is that fair to say? That's what you're like, it's not a third. It's not a rule. You're already breaking it. I don't know. I don't know. Anyway, I love this conversation

Menuez: cause you're not wrong. You're not right. It's a process that everyone has to come to for themselves and what works for them. But I, I would differ in one sense in that photography is not different than carpentry or making swords in Japan Caetano there is craft and to make a Katana that's going to last a thousand years, you're folding Shamani steel over and over and over it and there's a very specific way to do it to have a really good sword that will cut through bodies. They measure by the measure this sword strength. Like we're sharpness by how many bodies you can cut through with one blow.

Suzanne: So if you want a three body sword you got to have these certain things. That's the like of swords is the like of sorts. And I got to photograph the sword maker in Japan and I learned this stuff but I don't think garbage watched a lot of forged in fire.

Menuez: Well, I should go to that now that I may not get my shit, but I think that's, there's a craft element and like every craft you got there are step by step things you can do and but the mystery is does composition matter for the viewer emotionally or some biologic reason that forms memory? We don't know. I have a theory that that is true, but I like to be challenged. I like to look at stuff that surprises me. I don't want to look at everything that's exactly rule of thirds or whatever. I just think that we have to, if you use those and you learn those, then you have to kind of put it in here, the back of your mind and focus on what is important to you. Are a person, are you a person that's all about, you know, surfaces and pristine objects or are you about emotion and a mystery of what it's doing. It is to be human. I mean, what is it that really excites you? And so when you take out your iPhone and you're shooting your family, all that comes into play. You know, all of that comes into play and you could take a class about composition and may or may not help you. But um, I suspect that if people learn those techniques and then surpass it, go beyond that, like they put in their back pocket. It's something they could try or they could use. I think it will be useful for them. Interesting.

Suzanne: It's like the basic vocabulary for a language almost. You kind of have some key elements and then you can improvise or then you can make high coup.

Menuez: Exactly. Exactly. Exactly. And I think, I think it's on the, on the photographer, it's that push themselves and try different things. Like you said Michael, you know, you don't want to think about that stuff. You want to figure out what's important in the frame and then let things happen naturally. But I think, I think there is something to learning the craft. I think that's what's missing in the digital side. In fact, I would challenge you on that because the barrier to entry now is so low. The tea to do photography that's reasonably, you can actually look at it and see something that's astonishing and that has leveraged a lot of people that didn't know they had an, I didn't know they had creativity. That's exciting and it's sure it's killed my industry. So what

Rubin: I completely agree with you, it's like we're, we're on the dawn or were like entering a renaissance of creative photography where everyone, like literally everyone has a Leica practically in their pocket. It's not like it, but they have a great camera and they just don't know anything. I'm like, they need to learn from people like you who have walked around with a camera in their hand their entire lives because there's something to be learned that it isn't. You can put, you can pick your iPhone up, but you do get better at it and you do learn. Yeah, and a problem with the iPhone for a photographer

Menuez: coming to the iPhone is learning the vocabulary of the iPhone because it's got different lenses and it's got different exposure issues. It's, it's you know, you really, it's easier if you get an APP and put it in manual and you can control it like a camera. And that's easier to live with the limitations. But it also is the strength that it has built in auto everything. But for me, the reason I always liked ams and I always had an m with me even when I was shooting another brand. That's the Leica. Yeah, I just had a, like a m because I would do street photography with that. And it was a discipline because it's all manual. And I had to remember to think before I lifted the camera, oh, I have to open up for this one that's coming up. I have to start focusing towards infinity for this one.

Menuez: I have to think of terms of f stops and shutter speed. And it has to be this quick because I'm lifting the camera and that's what I'm thinking of it. And that's what, the other thing about composition to fault finish up on that, you know, Carnegie Persona said it's not enough to get the decisive moment. He actually said that it's not enough. And he, he said the photographer has to put that moment within a pleasing graphic composition. So if you like his pictures, that's the way he looked at it. Something graphic and, and he was using probably our styles mean pink golden rule thing.

Rubin: All right. We will come back to that idea that, is there anything, is there anything you wouldn't take a picture of? Like, do you have Wifi?

Menuez: Put my camera down a lot. When I was ending my news career, I'd still have done some news, but I remember shooting like the hundredth person in a forest fire, lifting their family photos out of the ruined house, you know, and I just was like, you know what I mean? The greater good theory is, you know, you're bringing a story to wider audience to help bring light to uh, help the situation or help injustice if that's the case, you know, and, and to some degree you're invading privacy and the people don't necessarily realize the implications of the picture being taken of them in a tragedy situation. And I just at one point started to limit myself and I guess it's part of growing older, you become like, it was all about getting the picture because you'd be fired, you know, otherwise, and you're competing with all these other photographers. But I think as I got older I was just like, this doesn't matter as much as the human being here. You know? I always felt that way, but I really started to act that way. So it's not that there isn't something I wouldn't take a picture of. I mean I photographed a c Csection, I don't recommend it.

Menuez: Okay. I'm telling you don't photograph that.

Rubin: I mean, could you have taken Dorothea Lange's migrant worker, the mother, like would you put your camera in her face and that horrible moment she's in or does that feel invasive?

Menuez: Everything is by the moment you can't know what Dorothea Lange and that woman experienced the eye contact to each other or how they were. There is so much that goes on in nonverbal communication and verbal communication. I go into sensitive situations my whole life. And the first thing you do, I mean, there's two ways to do it. You could try to get a picture because it's just happening and you get it. But when I do that, I immediately make eye contact and go to the person and start talking and explaining what I'm doing or connect with them. I think if we're going to make a picture that's meaningful, I, I have this rule if I'm going to, I actually do believe as the Mussai that I photograph for the cover of day in life of African and peed out 300 photographers for that cover the Messiah.

Menuez: I don't like to be photographed. They believe you're stealing their soul. And I kind of feel like that's pretty true. We're taking something. Therefore for it to be meaningful, there must be something given in return. There has to be an exchange in my mind, at least how I work. So that could be as simple as just introducing yourself, showing respect, hearing their story, finding out who they are. It might be a meal, it might be your life. You have to be willing to give it up to get you gotta give it up, whatever requires, I can give you one example if you want to turn it here. I was assigned to shoot homeless people in Phoenix in 1986 something in there for Fortune magazine. And I flew down from San Francisco and checked in the hotel, got my stuff together and just jetted out to downtown, which was block after block, after block, after block of encampments, homeless encampments.

Menuez: It was the height of it, it was just madness. And there was uh, a man standing in, um, a section of tense and I thought that was really interesting and I didn't know what to do and I just started to shoot a little bit cause no one was getting, I wasn't getting any negative vibes and tons of people had been through there. So I just started to frame up a shot and this guy came up to me and said, hey, you know, MF, what are you doing here? And uh, he actually had a weapon. He had a knife with him and he started to kind of grab my arm and was threatening me and I said, oh, I'm with the press, I'm here to shoot the homeless story and tell the story. And he goes, Oh yeah, where's your press pass? I said, and I said, oh, I left it back in my hotel and I could see his, his I, you know, I did a lot of drugs stories, the Oakland drug wars and crack dealers and I could just see he was just, he was flying, you know, so I could sense in the moment that he wasn't really there.

Menuez: He was just as high as a kite. And I said, you know what, let me go back and get it. I'll come right back here and I'll show it to you. And he goes, okay, I'll be right here. And I get back in my rental car and I drive back to my hotel and I get my press pass. Cause I wasn't freaking mind. I get it on the desk where I had left it and I drive right back and the guy has completely forgotten about me. And I go and find him and I show my press pass and like that I'm in, he's my guide. Wow. And now I have a guide to the story and now I've made friends. So I think wherever you go in every community, there's somebody who's a leader who's, who's important in whatever that many culture is. You have to figure that out and make connections with people. Um, you can only steal photos so much without having to give something back even to get busted.

Rubin: Do you think this is something that um, I think consumers with their iPhones main be learning about or have to kind of come up against, which is how invasive it is to have a camera pointed at somebody and that developing that kind of trust, I think they pulled their cameras out all the time, but to get really good pictures, they need to confront what they're doing. Um, does that, is that a thing? Do you

Menuez: yeah, I think it's a threat. I think it's a threat when you take a camera now and pointed at someone, especially a camera with a long lens, it's a threat perception now. It's, it's, it's not even an invasion of privacy. They just don't know what you're pointing at them right away and what it is and what your agenda is. And if you're, if you're in New York City, everybody has an agent. So it's like they own their brand. All right. I mean, I'm telling you anywhere I walked all the five boroughs and everybody's has is aware now. So

Rubin: what's a photo on your wall right now that you took that you have of that I took? Um, well one is the of what you took in one is that you didn't take that you love. Oh look, there's the Hurwitz you have somewhere where it's up there. Wow.

Menuez: Jim Marshall. I'm doing this in reverse. Here's one of mine.

Rubin: Lot of Erwitt's. That's interesting. Oh, I love that. What does that picture? This is a

Menuez: young woman at the Hacienda where they make Tequila for in the IPV for [inaudible]. Uh, when I was doing, I did a four year project about Tequila is a symbolic way to understand Mexican culture. Hm. Um, yeah, Elliot was kind enough to write the introduction to my last, my most recent book, fearless genius in it, a real mentor and different,

Rubin: um, I'm, uh, I'm this huge Elliott Erwitt fan. That's cool. Were you a magnum photographer? Are you

Menuez: no, no. That was my goal. That was my dream on Dennis, uh, wanted me to consider it. You know, it may be, you still have, maybe it will still happen. I just went in a different direction. What makes them different? Well, there are a commune. I mean there are collective and they, they, there is a financial burden that some photographers there feel, some don't. I think it's strength in numbers. I think it's a really, you have to look at the history, how they started to fight against publishers who were taking rights and trying to pay nothing. A magnum is the most important event in organizing photographers before the ASM. P You know, in the SNP and AP, these are all really important organizations cause everyone wants our stuff for free and to crush us basically. But I kind of found my own path and there was an opportunity where I might've been able to go there, but I, I, I'm, I'm on a different path. Wow. That's good.

Suzanne: Yeah. What is one word that makes your photos uniquely you or uniquely yours?

Menuez: I would hope it's, uh, empathy. Uh,

Suzanne: I see that in your photos. I mean there's a quote that I actually had pulled prior to this interview that I love that's um, we're primates. We look for IEDs, expression and emotion and the human face. The face is how he connected with people. And I see, I see so much emotion and um, kind of connection with your subjects and your in your images. There's a lot of empathy there.

Menuez: Thank you so much. Thank you so much for saying that.

Rubin: This is great. I mean, Doug, I could talk to you all day. This is, I mean, I don't want to, I don't want this to stop. Is that like a great date? I Dunno.

Menuez: I love you guys. You guys asked the best questions. We should talk all day. We should get on another conversation. But I love what you guys are doing and I love that you're bringing conversations like this to people who are discovering photography. I think that's really important.

Rubin: We were at an amazing moment in history where everyone's got these cameras and I think it big brings up this question of like, why do we take pictures? Not just how, but like what is worth photographing? What? Why are we even doing this? There's so much data.

Menuez: I'll have to show you one more thing before I go to my studio here. This is what's on my wall that I see every morning.

Rubin: What is it worth doing? Nice.

Suzanne: Well first and foremost the thank you Doug and it's been an absolute pleasure. Our show was recorded and produced in San Francisco. It's got to neo modern.com/podcast to get show notes, see photos and post comments and please leave reviews and ratings on iTunes. Don't forget to subscribe. We

VO: get new listeners from you telling your friends and spreading the word. If you know someone who might get something from us, Doug, send them a link and thanks to Mitchell foreman for it in music and all of you for hanging out with us. We appreciate your attention and hope we've given you some things to think about. Until next time.

Rubin’s Portfolio of Photography | Rubin’s Instagram (@droidmaker)

Suzanne’s Instagram (@sfritzhanson)

If you like our show, please subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, or your favorite podcasting app, and please rate the podcast. And don’t forget to join the Neomodern Facebook group to discuss the show, share your photos, hear about specials for printing or framing your best images. Thank you!